CLEMSON — Erik Bakich can string together so many words of admiration for the late Pat Tillman that he has to stop after several hundred and clarify.

Yes, Bakich took his wife to the South Pacific island of Bora Bora after their wedding because that is where Pat and Marie Tillman honeymooned. And, yes, Bakich's son, Beau, took his middle name Patrick from the hard-hitting safety who sacrificed an NFL career to serve in the military.

But as Clemson's baseball coach gets rolling about Tillman's toughness, his selflessness, his passion for life, he has to make clear the nature of their relationship. Bakich played baseball with Tillman's younger brother, Kevin, growing up in San Jose. Pat was more of a distant figure.

"He was almost like folklore, someone you read about," Bakich said, raising his hands to touch the imaginary pedestal where Pat stood.

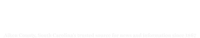

Bakich wasn't close, but close enough to be influenced by a hometown hero. He watched an unheralded recruit become an All-American at Arizona State, a seventh-round pick became a star in the Cardinals' secondary.

Tillman left it all behind.

"He will always be one of the people in my lifetime I will always look at as a model of what a true American hero looks like," said Bakich, the son of a Vietnam War veteran and the grandson of a World War II vet.

The mythology surrounding Tillman is complex, because 20 years ago, on April 22, 2004, he was killed in Afghanistan and the circumstances were initially warped to fit a more heroic narrative. Tillman's family fought for the truth — it was a friendly fire incident — to be acknowledged.

Clemson coach Erik Bakich grew up with Pat and Kevin Tillman in San Jose. He tells the story of Pat, who died in Afghanistan on April 22, 2004, every year to his baseball teams. John Carlos II/Special to The Post and Courier

But everything real about Tillman inspired Bakich. He has, in turn, shared Tillman's story with athletes at Maryland, Michigan, and now Clemson, flipping through a 9/11 PowerPoint that starts with the attacks but transitions to an unpretentious Tillman, riding a bicycle, shirtless, to Cardinals training camp.

The strap of a well-stuffed gym bag runs a diagonal across Tillman's chest. There are brown bags gripped in his left hand, like the stereotypical lunch pail.

Next, a video plays, and Tillman speaks.

"A lot of my family has gone and fought in wars," Tillman says, "and I haven't really done a damn thing as far as laying myself on the line like that."

Man, not myth

In truth, Tillman never offered a statement on why he enlisted.

According to the documentary The Tillman Story, the previous sound bite was from a series of interviews the Cardinals conducted with players after 9/11. Pat, born into a family with an extensive military heritage, spoke about his love of country. But he never entertained questions about his decision to join Kevin, a MLB prospect in Cleveland's farm system, with the Army Rangers.

He wanted to be like any other soldier. No fanfare.

Unfortunately, Tillman racked up too many big hits — 340 tackles in four NFL seasons — to be anonymous. It was news when a 25-year-old fan favorite turned down a three-year, $3.6 million contract to deploy to Iraq.

He never explained why. But his actions were inherently selfless.

"It's a throwback to a generation I think we all genuinely wish more people were like today," said Bakich, who will criticize the "independent contractors" in baseball who value their "Twitter swing" above team ball.

Bakich, whose default mode is friendly and even-keeled, like it's 70 and sunny in San Jose, believes in carrying oneself a certain way. He's unabashedly patriotic, drilling players on how to stand for the national anthem: Heels together, toes spread apart at a 45-degree angle, back straight, left hand grabbing the piping of the pants, hand on heart, hat over shoulder.

Every day, the 46-year-old coach practices the relentlessness he preaches, not above shagging fly balls or bench-pressing alongside his athletes.

It's nothing Tillman wouldn't do.

Bakich thinks back to a summer in San Jose working construction for his friend's father. They were teenagers, not exactly happy to be there. A curiosity popped into Bakich's mind.

He asked his friend's dad: Who is the hardest worker you've ever had?

"Without hesitation," Bakich said, snapping his fingers, "he said Pat Tillman."

It was something to learn Tillman — the Pat Tillman — wasn't above laying asphalt in San Jose.

Tillman was unique, growing up in a home with no television and one phone. He was a full-blooded American with a knack for dropping F-bombs, but Tillman also read the social and political commentator Noam Chomsky.

As painful as it was for ball carriers to run into Tillman on a football field, sports reporters suffered when they tried to get the Leland High star to talk about himself. He'd roll his eyes, then defer credit to his coaches and teammates.

Kevin's intensity was similar, only he mainly smashed baseballs. Bakich recalls attending a party as a junior or senior in high school, and Kevin threatened a similar level of force on a half-dozen bullies who picked on a friend.

"All of them left the room, wanting no part of Kevin Tillman, because he's a Tillman," Bakich said. "I just remember thinking 'These are the toughest guys.'"

These memories are nearly three decades old, but Bakich smiles as they reemerge. The Tillmans stood for everything he admires.

Passion, brotherhood, sacrifice.

"I wish he was still with us," Bakich said of Pat, "but I want to make sure we continue to tell his story. It's a story everybody needs to hear."

Being like Pat

Bakich likes to say Clemson starts every day in "the classroom," and every Sept. 11 begins with a history lesson.

On a projector screen, Bakich's players watch as the second plane hits the South Tower and fire slices through glass and steel.

They see "The Falling Man" photograph, a poignant reminder that some chose to jump from the World Trade Center rather than burn.

As freshman Jarren Purify recalls that PowerPoint, he remembers, "You can be taken from the earth at any second. It's that fast."

This is one of the heavier lessons Bakich shares with his players. Other days, he teaches them how to breathe in stressful situations, how to focus their "Warrior Dial" and play with passion but not out of control. Sometimes, Bakich just wants to talk about being a "good dude" on and off the field.

The best dude was Pat Tillman, willing to roll up to Cardinals training camp, shirtless, on a bicycle.

Ask the Tigers, and they recall Tillman on his bike. They smile, having seen a picture of their coach, newly married, posing with his bride in front of the aqua-colored waters of Bora Bora. They know Beau Bakich's middle name.

More than anything, they relate to Bakich's reverence for his hero.

"To sacrifice that, to go fight for our country, is a big thing," junior Austin Gordon said. "It's a big thing for this program. We don't take anything for granted. We take everything into perspective. It can be done — in a blink of an eye."

Tillman never said why he enlisted. But it's understood, according to The Tillman Story, that he was offered an early exit from his service commitment, opening the door for an NFL return. Even if he was displeased by some of what transpired during his tour in Iraq, Tillman declined.

He committed to three years. He insisted on serving three years.

Any sacrifices the Tigers make on a baseball field pale in comparison. Every year, Bakich strips players of access to facilities in the fall and deprives them of gear. It's a matter of principle — nothing is given, everything is earned.

Near the end of the Tillman PowerPoint, one slide simply reads "PASSION." This is non-negotiable in Bakich's program, along with a list of edicts on the next slide, including "Be a Good Dude" and the "I/We Challenge" where players must use "we, our, us" rather than "I, me, my."

The last slide is Tillman-esque, as well, in its use of an F-bomb, but in a positive way: "Let's F'n Grow."

"We always got each other's backs. We want to be like Pat," said Jimmy Obertop, the Michigan grad transfer who has heard Bakich's 9/11 presentation several times. "We want to serve others like he served the whole country."

So they stand for the anthem. Toes pointed, back straight.

They pick each other up when they fall behind, claiming numerous comeback victories during a 32-7 start to the season.

They aren't individuals at the plate. The Tigers execute as one, and they refuse to say "I" in press conferences.

They have learned these values from their coach, who found inspiration from one of his contemporaries in San Jose. More than folklore, Tillman has a legacy.

"How much of a role he played in Coach Bakich’s life, that was almost like his brother," Purify said. "Hearing that story, and seeing how passionate EB is, just makes everybody on the team want to play for each other.

"These are your brothers."